How Black art movements inspired the design of a new typeface

The Background

“If you ask anyone in Britain what British black culture is, they’ll probably say Grime,” says Cephas Williams, entrepreneur, photographer and founder of 56 Black Men and Drummer Boy Studios.

It was Black history month and Represent, Dentsu’s network for employees from a Black, Asian and minority ethnic background, had been putting on daily events, all with great content. A conversation between Williams and isobar’s Chris Roye caught my attention. It was packed full of observations that helped me to look at things from a different perspective, but it was this statement, in particular, that stopped me in my tracks.

The same is true the world over. Many never look past music to explore Black culture further and it got me thinking about Black art movements with a positive message, devoid of any negative stereotypes.

This investigation inspired me to design a new typeface: Boykin.

What I Did

I started with two personal favourites: AfriCOBRA and Afrofuturism.

AfriCOBR, African Commune of Bad Relevant Artist, explain the movement in their 1968 manifesto: “We strive for images inspired by African people/experience and images which African people can relate to directly, without formal art training and/or experience. Art for people and not for critics whose peopleness is questionable. We try to create images that appeal to the senses - not to the intellect.”

AfriCOBRA delivers on its manifesto promise; it looks nothing like anything you’ve seen before.

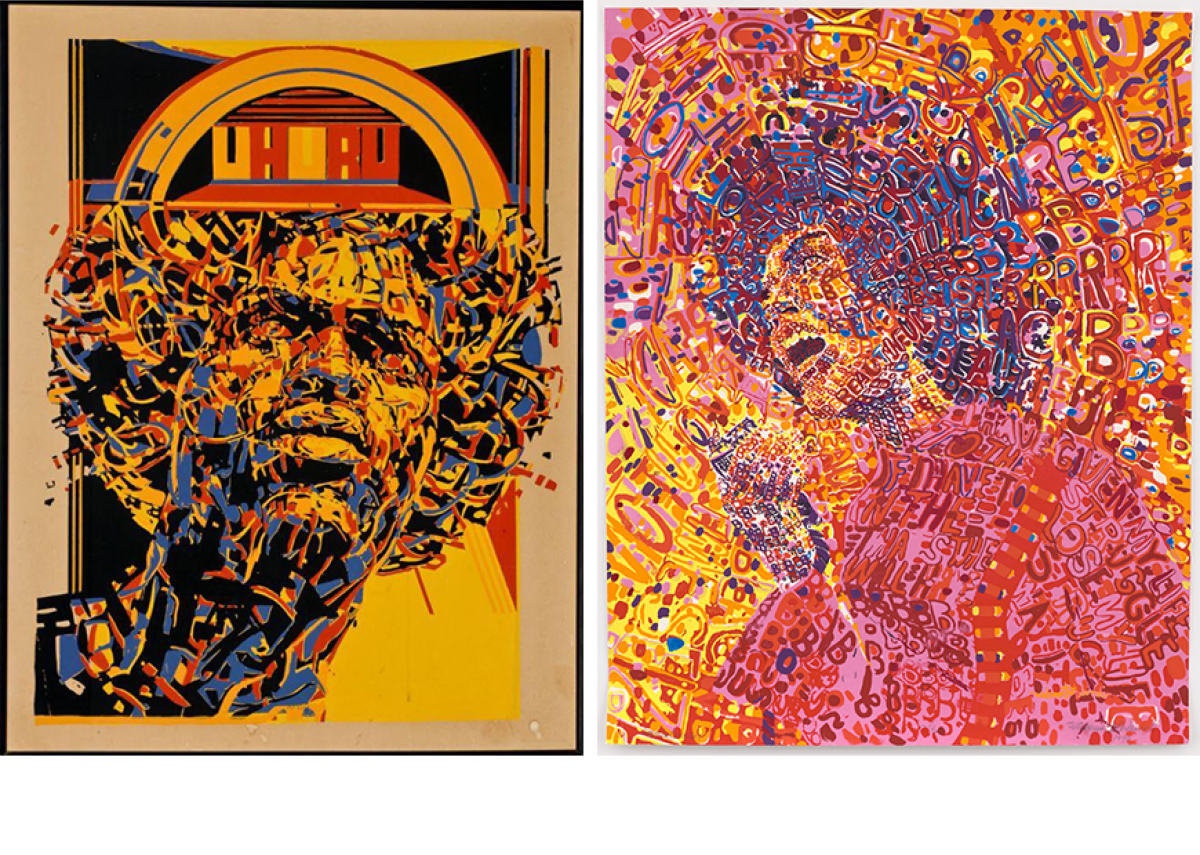

Vibrant colours punch out of the canvas in a mosaic of shapes, words and stories, which coalesce to create an even greater image. Wadsworth Jarrell’s ‘Revolutionary’ is its perfect embodiment, while Nelson Steven’s ‘Uhuru’ leaves you scratching your head, wondering how Pollock-like paint splats can unify into an incredibly uplifting portrait of a young Black man.

Afrofuturism

The term Afrofuturism was coined by white author, Mark Dery, in his essay “Black to the Future” 26 years ago: “Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth century technoculture — and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future — might, for want of a better term, be called Afrofuturism.”

Afrofuturism has outgrown its original definition to encompass any imagining of a Black future, with arts, science and technology seen from a Black perspective, and not just by African-Americans but by the whole Black diaspora. Its uniqueness lies not just in the fact that the movement has not been defined by its collective members, but rather, that there are no collective members at all.

Accessible to anyone, unlike AfriCOBRA, this fascinating, democratised movement doesn’t have a definitive look, but is still instantly recognisable. Look at the futuristic architecture of Wakanda in Marvel’s ‘Black Panther’ and you’ll know that it’s not been designed by a Western culture.

The Gee’s Bend quiltmakers

Then my partner, who is herself of mixed heritage, told me about an artist group I hadn’t yet come across: the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers: A small Black community of around 700 in Gee’s Bend Alabama, most descendants of slaves from the Pettway plantation.

Geographically remote, Gee’s Bend resembles an inland island, surrounded on three sides by the Alabama River. Their unique style has emerged without outside influence and has been developed for over a century and a half, evolving into five types of quilt style: Abstraction and Improvisation, Housetop and Bricklayer, Patterns and Geometry, Sears Corduroy and Work Clothes. I was fascinated by these quilts; to my Western eye they look like some avant-garde art movement emanating out of Europe.

Their use of geometric shapes and pattern could easily come straight off the shop floor of the Weaving Workshop at the Bauhaus. There’s no way the quiltmakers could have seen Bauhaus textiles, but you can’t help wondering if the Bauhaus somehow saw the work of Gee’s Bend?

I really wanted to share what I’d discovered and started to write something to send round the office. At the same time, I had been getting itchy feet to design a new typeface. I try to produce one a year and, well overdue, was getting frustrated that I hadn’t done anything I liked.

Looking at these three art movements gave me a new direction.

AfriCOBRA’s incredibly graphic interlocking shapes were a wealth of inspiration for letterforms, while Afrofuturism’s ability to reinterpret objects from a differing viewpoint allowed me to start from a place I never had before. Instead of finding a shape that defined the typeface and was then present in all the characters, each character shape had to represent an idea.

But it was looking at the patterns and geometry of the Gee’s Bend quilt makers, especially those of Nettie Young, Mary Lee Bendolph and Loretta Pettway Bennett that really sparked the idea for my font.

Their use of negative and positive space is particularly interesting, and taking this duality, I designed a font that had both in a single character.

For the quiltmakers, this is not just a style, it’s a visual conversation that’s carried through generations. The stories of families who live just yards away from each other can look completely different, as uniquely personal as the conversations they represent. It’s the African musical tradition of call and response communicated in textile. Although my font isn’t passing on stories and heritage, it echoes the style of these quilts.

Paying homage to its inspiration, I named it Boykin, after a small town at the heart of Gee’s Bend.

Listening to just one intriguing talk, took me to the tip of culture from the Black diaspora. And just a small taste was enough to drive me to create a typeface, write and share what I had learned. So no, Black culture isn’t just music. I would encourage you to go deeper, much deeper. It’s not only incumbent upon all of us to educate ourselves to improve our understanding and appreciation of it, the process can spark new thinking and creativity, which benefits us all.

If you enjoyed this article, you can subscribe for free to our weekly email alert and receive a regular curation of the best creative campaigns by creatives themselves.

Published on: